Don McCullin

Don McCullin grew up on a London

council estate and at age five, was evacuated to Somerset. Seperated from his

sister, who was placed with a much wealthier family, McCullin developed issues

about class and poverty; his affinity to persecuted peoples developed later through

being beaten at a later placement. McCullin left Art College to support his

family aged fourteen, following the death of his father. Severely dyslexic and

having not done well in school, McCullin was a self confessed tear-away until a

gang acquaintance was involved in the murder of a police man. McCullin, having

photographs of the gang was immediately in demand with the press; this was the

beginning of a lifelong career in photography.

McCullin’s photography is

described as exceptionally powerful and technically sound. He uses relatively

simple equipment, never a flash and rarely has a need for cropping or

manipulation; he is instinctively a great photographer. He always does his own

printing and mainly in black and white with heightened contrast to enhance

impact, to make those images really stay with the viewer as they do with

him.

McCullin worked intensively as a

war photographer, to the detriment of his first marriage until the early

eighties when issues over opposing ethos lead to his dismissal.

Turning to work such as advertising to pay for travel, McCullin explored parts of India and Africa, writing books such as ‘Don McCullin in Africa’. Whilst in England, McCullin spent time photographing homeless people for a story about derelicts, those pushed aside by society. Cold and with a sense of discomfort, McCullin describes the excitement of potentially encountering an amazing scene; as with his war photography, he was looking for the truth and often found it in the gaze of his subject looking directly at him. He once said that as he worked he ‘looked into people's eyes and they would look back and there would be something like a meeting of guilt’. It is this that gives depth and compassion to his images.

McCullin believes that seeing, really seeing has nothing to do with photography; photography is just about showing the truth of that. The most important thing in his eyes is your emotional approach and the emotional commitment to where you are and what you are doing; to him, the technical side is secondary.

Turning to work such as advertising to pay for travel, McCullin explored parts of India and Africa, writing books such as ‘Don McCullin in Africa’. Whilst in England, McCullin spent time photographing homeless people for a story about derelicts, those pushed aside by society. Cold and with a sense of discomfort, McCullin describes the excitement of potentially encountering an amazing scene; as with his war photography, he was looking for the truth and often found it in the gaze of his subject looking directly at him. He once said that as he worked he ‘looked into people's eyes and they would look back and there would be something like a meeting of guilt’. It is this that gives depth and compassion to his images.

McCullin believes that seeing, really seeing has nothing to do with photography; photography is just about showing the truth of that. The most important thing in his eyes is your emotional approach and the emotional commitment to where you are and what you are doing; to him, the technical side is secondary.

Often asked, ‘Do you hide behind the camera?’

McCullin considers this a ridiculous question; hiding behind the camera would

be tantamount to hiding your own emotions. McCullin’s ethos is to be

there, feel it, live it, look at what’s in front of you; I am inspired by

McCullin’s work but I what truly inspires me is the ethos of committing

emotionally to a situation, in a bid to capture so much more than

visual impact.

Jason

Bell

Jason Bell is an English portrait and

fashionphotographer who shares his time between London and New York,

working for Vanity Fair, Vogue, Time and other magazines. Many of his

photographs, including his set entitled, ‘An Englishman in New York’ are in the

National Portrait Gallery. Having fallen for New York through a picture in

his childhood home, Bell eventually moved there and loved the new found freedom

he discovered there. A chance conversation lead him to the decision to discover

through photography, why so many others had made the same move. Photographing

celebrities such as Kate Winslet and Sting as well as everyday people, a rat

catcher, a pilot, Bell also considered the question, why had he himself made

that move.

Like London, New York is a well photographed city so creating something new proved quite a challenge; Bell aimed to avoid clichés by thinking what he had noticed when first moving to New York. While photographing many of his subjects at work, he opted away from the obvious; historian Simon Schama, rather than being photographed at the university, was taken to the subway whereas author Vicky Ward sunbathed unnoticed by city crowds showing the unshockable nature of the New Yorker.

Like London, New York is a well photographed city so creating something new proved quite a challenge; Bell aimed to avoid clichés by thinking what he had noticed when first moving to New York. While photographing many of his subjects at work, he opted away from the obvious; historian Simon Schama, rather than being photographed at the university, was taken to the subway whereas author Vicky Ward sunbathed unnoticed by city crowds showing the unshockable nature of the New Yorker.

‘What do I remember noticing first when I came

here? Seeing an expensively dressed woman in her 80s on the Upper East Side

bending down to pick up dog shit with a perfectly manicured hand.’ Jason Bell

On 23 October 2013, Bell took the official

christening photographs of Prince George. Very different from his New York set,

these images could have been taken by any technically aware photographer.

The Guardian newspaper describes the image of the

core family as ‘pretty perfect as a document’ and goes on to discuss the

technical qualities of the image. This image, to me looks like every image ever

taken of the royal family; this is work. Bell may have enjoyed spending time

with the family but I doubt that he got the same satisfaction taking this shot

as he did creating his ‘Englishman in New York’ collection.

Some shots are more natural in appearance, the one

of the family framed by the window hints at a more normal, everyday world which

they must inhabit sometimes; the slightly desaturated colours enhance the

traditional feel of the image. Bell has also captured Kate’s love for her baby

as she looks at him cradled in her arms. Beautiful as they are, it is clear

that creativity is restricted and Bell’s voice is clearly muffled.

One of Bell's favourite shots:

Yousuf Karsh

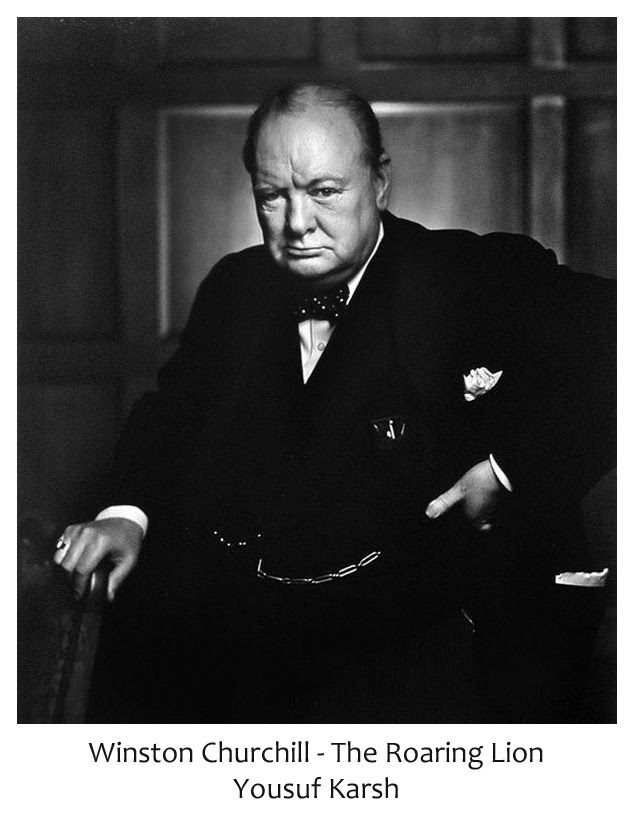

Yousuf Karsh, who shot to fame following his portrait of Winston Churchill; The Roaring Lion, has in his portfolio, images of many great heroes. Karsh’s images show great variety in posture and lighting while capturing brilliantly the individual character of the subject; as stated in the L.A. Times, ‘Each picture captures not only an image but a personality’. The body language, direction of gaze and hand gestures work together with lighting and effects to hint at the type of person being portrayed.

Yousuf Karsh, who shot to fame following his portrait of Winston Churchill; The Roaring Lion, has in his portfolio, images of many great heroes. Karsh’s images show great variety in posture and lighting while capturing brilliantly the individual character of the subject; as stated in the L.A. Times, ‘Each picture captures not only an image but a personality’. The body language, direction of gaze and hand gestures work together with lighting and effects to hint at the type of person being portrayed.

His portrait below of Albert Einstein is lit from slightly behind so that the light skims across his face, highlighting the deep wrinkles which show great wisdom and character; true to type, Karsh has captured the pensive look on the academic’s face. French author, François Mauriac’s silhouette is given an aristocratic feel using edge lighting to highlight only the edges of his noble features. Karsh’s portrait of playwright, Bernard Shaw is lit from a high angle creating strong highlights and shadows in his face and clothing; Karsh has perfectly captured Shaw’s quizzical demeanour.

Karsh’s became well known for his hero worshiping ethos and as a result, his subjects knew that going in front of his lens would bring them iconic status. He was trusted by all to bring out the best in his clients, boosting their public persona:

There is a brief moment," he believed, "when all there is in a man's mind and soul and spirit may be reflected through his eyes, his hands, his attitude. This is the moment to record. This is the elusive 'moment of truth.”

It has been written that Karsh’s motivation stemmed from a belief in the dignity, goodness and genius of human beings.

Karsh’s work has been in a variety of mass media, including postage stamps and currency and is recognised in both European and North American culture.